The Benefits of Weekly Periodization in Pitch Sizes for Football Training.

IIn an article published in Dagens Nyheter on April 6, 2023, titled "This is how the future national team should not fall behind: 'We need to change some of the training,'" an ongoing study by the Swedish Football Association (SvFF) in collaboration with Umeå University was presented. The study followed 61 Swedish girls' national team players aged 15–18 years from 2019–2021 and showed that young players need to incorporate more high-speed training in their routine (where high-speed training is defined as >15 km/h).

The study on the physical load of young female football players, both in training and matches, showed that the total distance covered was understandably longer during a week of combined training than in a single week's match.However, the players ran further at high speeds in matches than during a whole week of training.

The high proportion of starts and stops in the GPS data from training indicated a lot of so-called small-sided games.

Researcher Helena Andersson:

Previously, it has been said from a fitness training perspective that small-sided games provide very good training, which is still true. But some of this training needs to be replaced with exercises that challenge high-speed running.

But sometimes the pitch can be too small, and some teams have very thin squads, which means they cannot play on larger pitches.

Helena Andersson further responded to questions from DN's Lisa Edwinsson:

Are you saying they don't have access to a full pitch, or is it a tradition to train with small-sided games?

It’s a combination, I would say. When we brought this up at a joint conference, someone mentioned, 'In our area, in the big city, we only have a half-pitch for girls aged 15.' So, we have to find other ways to reach high-speed running.

If we turn it around, what are the risks of not changing the training approach?

The risk is that the difference in load between training and match becomes larger and larger. And then the players are not physically prepared for match load.

Helena Andersson is, of course, correct that speed is crucial in modern football and that training design must be representative for players to be physically prepared for match demands. And yes, there is too much training on small areas relative to the number of players, such as in the above-mentioned small-sided games.

Although much research remains to be done in this area, it is probably easier to achieve a correction in training design and thus an adjustment in training load than the responses in the article suggest. Yes, there may be limitations in purely football-related training (i.e., without resorting to isolated running training) that can be conducted if there is limited training space or too few players in the squad to play on a larger scale during training.

However, in my experience, two underlying problems often cause players to get too little high-speed training time:

The club’s/team’s/coach’s game and training philosophy.

Lack of knowledge about weekly periodization in pitch sizes.

Looking at point 1, the game and training philosophy, it has been very trendy to focus on counter-pressing training in recent years. Coaches have seen Jürgen Klopp’s Liverpool crush opponents' build-up play, win the ball high up, and create chances, and they want to replicate this with their teams. At the youth level, this is an easy way for a coach to achieve quick results with their team—results that are often mistaken for player development. This obsession with high-intensity pressing/immediate counter-pressing after losing the ball leads coaches to prioritize drills on too-small areas that reward the chasing players for short, intense stop-start training. An example of a drill that is (mis)used for this purpose is the so-called English square or three-zone game.

The problem of too much training in too small areas is often exacerbated by another trend: the game philosophy that "we should be a team that plays beautiful football," where "beautiful football" is interpreted as a team being able to tiki-taka its way out of high pressing. "Players need to get better at handling the press" becomes synonymous with "players must be able to handle the ball in small areas." The focus of training becomes even more short, intense stop-start training.

A deeply rooted philosophy or working method can be difficult to change, but point 2 can be solved through simple education. This can, in turn, force a solution to point 1, thereby creating the conditions to correct the difference in load between training and match in terms of high-speed running.

Weekly Periodization in Pitch Sizes for Football Training

The first question we must ask is how large an area we should use for a specific drill.

Often, when a coach has used a drill several times, they settle on a "standard size" for the drill based on the number of participating players—a size that makes the drill "work."

The principles of representative training design lead us to the next question: does this size reflect the reality our players face in matches?

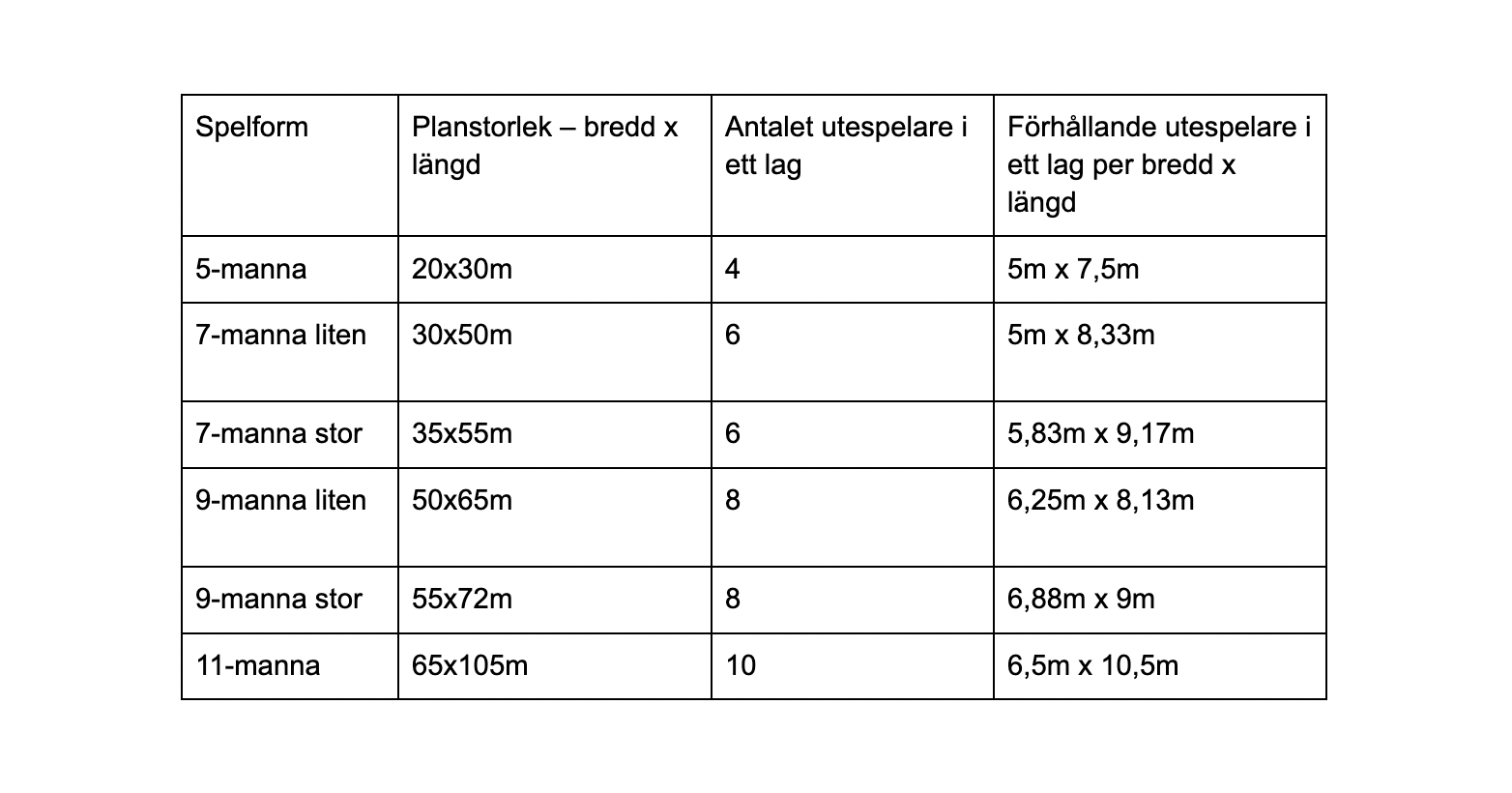

A simple rule of thumb for pitch size in training design for adult football is 6m x 10m (width/length) per outfield player in the team, based on an 11-a-side pitch (approximately 60m x 100m). The table below shows how this ratio looks in other formats of the game:

How could a weekly periodization in pitch size look?

Let's take an 11-a-side team with three training sessions per week as an example. A weekly periodization could look like this:

One session based on a ratio of 4:6.5

One session at 5:8

One session at 6:10

Where I disagree with the article is on the difficulty of implementing this in Stockholm where you “only” have half a pitch. It can be done on a quarter pitch! It’s just about adjusting the number of players—for example, for 6:10 on a quarter pitch (about 30x50m), play 5+GK against 5+GK with two resting teams, involving 22 players.

But this doesn't only apply to play during training. Much can be gained by using the same drill but periodizing the size as well, e.g., the English square. This opens up completely different affordances (possibilities for action) related to the need to develop entirely new technical skills, such as the ability to play longer passes, make wall passes over 10m distances instead of 3m, which in turn develops a different football physiology.

Periodization of playing areas in training design must be planned into the training week and has several benefits:

A football fitness aspect – to replicate the distances players need to cover in matches.

A relational aspect – it is one thing for a team to spontaneously create zigzag passing sequences in tight spaces in small-sided games; it is another challenge entirely to maintain these relational aspects over greater distances, where, for example, a wall pass may require a run of 15–20m to receive the return pass.

A technical aspect – If we train in small, tight spaces, the type of technique players develop will often involve quick flicks, short passes, and quick directional changes with the ball—short-distance skills. If we train on larger pitch sizes, players will need to play longer passes, drive the ball, and thereby develop appropriate techniques for those distances.

A shared affordance aspect - both in attack and defense. When learning fundamental defensive principles, such as press and cover/support in a 2v2, the distance the ball travels when an attacker passes to another is a key factor for defenders to learn the basic switch from press to support that needs to happen. Pitch size in training design is a key element. In attacking play, if the pitch is very small, many of the shared affordances are perception-(re)action-based, where there is no time or space for the passer to develop an ability to see and influence the opportunities to act for the receiver of the pass. Dennis Bergkamp said: "Behind every pass, there must be a thought," and we must give players the space to develop this ability.